Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own (1929) has a superb phrase for a certain kind of joy: “the lamp in the spine.” This is in the context of eating: “One cannot think well,” Woolf writes, “love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well. The lamp in the spine does not light on beef and prunes.” But for me the phrase has long held power as describing the pleasure of intellectual work. When it comes, this feeling is suffused with a strange kind of almost physical pleasure, difficult to vocalise actually — which makes Woolf’s phrase, both figurative and bodily, enigmatic but exactly evocative, so appropriate. Finding new things, threading new connections: the lamp in the spine lights up.

The lamp is lit again. I am in new surroundings with new trajectories of research — and have been so excited to begin. After the three years of postdoctoral work at Nanyang Technological University, in July I moved to an assistant professorship in urban history at the College of Integrative Studies (CIS), Singapore Management University (SMU). Out from Jurong, sat snug now at the foot of Fort Canning Hill. I have a room of my own and space and time now to work. Three major things keep me busy.

Pests Book: I am revising Liberating Parasites: Pests in British Malaya for publication, aiming to submit the dossier in February 2026 and now going through it line-by-line, cut-by-cut. This manuscript was written in maddening circumstances: in Hong Kong, 2019-2021, being battered round the head first by protests then covid. The manuscript tastes of it: late nights, the eight coffees a day, the frenzy of finishing gives the prose a certain mad tang. But for all the messiness, it has been enormously exciting to return to it. Its arguments are strong, I think:

- that the elasticity and generativity of the concept of “the pest” provided opportunities for all kinds of different actors (colonial legislators, chemical companies, entomologists, etc.), who thereby preserved this vague category even at a time of increasing scientific specialisation

- that colonial economic and infrastructural transformation in Malaya provided a glut of opportunities for certain insects to flourish and spread, even as broader ecosystems were wrecked, and that these shifts served to frame/interpellate these insects as “pests” (as I argued in my 2022 Roadsides piece: new roads meant lalang grass meant locusts, the insects repurposing an infrastructure of extraction; the spatiality of the road making the locust come to notice)

- that there was great multiplicity in colonial responses to insects/pests. An exterminatory degradation of the pest was paralleled by fascination and disquiet — especially that insect pests indexed disordered worlds, the colonial disruption of the landscape become manifest. What I am able to do much better now than I could in 2021 is to write this section within the broader longue durée of Malayan/Malaysian ecology. Figures such as Jack Ralph Audy, whom I wrote about in Medical Anthropology in 2023 bridge the emerging ecology of interwar Malaya, which I shall write about in the book, with the explicit ecological concerns of the postwar world.

The task now is to make these arguments clearly. Adorno is the great model of argument-making, combining a sensitivity to paradox with economy of expression. “The thicket is no sacred grove,” as he writes in Minima Moralia (1951). “Precisely the writer most unwilling to make concessions to drab common sense must guard against draping ideas… in the appurtenances of style.” Rephrasing, bulking, extending, polishing, contextualising — and actually quite good fun.

Otherwise work continues on two new projects.

The first situates the history of the Migratory Animal Pathological Survey (MAPS) in its Malayan context. I want to argue that postwar Malayan ecology was instrumental shaping the contours of this project and therefore the broader history of avian zoonosis. Warwick Anderson gave me a push to work on this at the HOMSEA conference in 2023 and I’ve been needling at it since. I presented a paper on it for the first time at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) in April 2025 and again at Hong Kong University (HKU) that same month and shall present on it again at the Asian Association for Environmental History conference in Takamatsu this month, with my draft paper to be submitted in October 2025. From Malaya, this project looks northward — up to Japan and far eastern Russia, with the provocation of being the first person to write on the “Siberian history of the Malaysian rainforest”. More to come.

The second project focuses on the history of the Coconut Rhinoceros Beetle (Oryctes rhinoceros) and the network of biological control efforts spanning both Southeast Asia and the South Pacific which developed between the 1910s and the 1970s. From Malaya, this project looks eastward — connecting Singapore to Tokelau. I am currently drawing together a grant application for a research assistant, a trip to Nouméa, New Caledonia, and a conference on histories of biological pest control to be held at SMU in 2026/2027. More to come too.

Other ideas wash about in my mind. Infrastructural bacteriology. Villain-hitting under flyways in Hong Kong. Coprolites and WWI munitions. Rainforest canopies and boardwalks. One model for writing history: Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow.

Reading: As during this summer, lots of Marshall Sahlins; Paul Theroux’s abysmal Saint Jack (1973), a Singapore novel which would be exotic but is actually dreary.

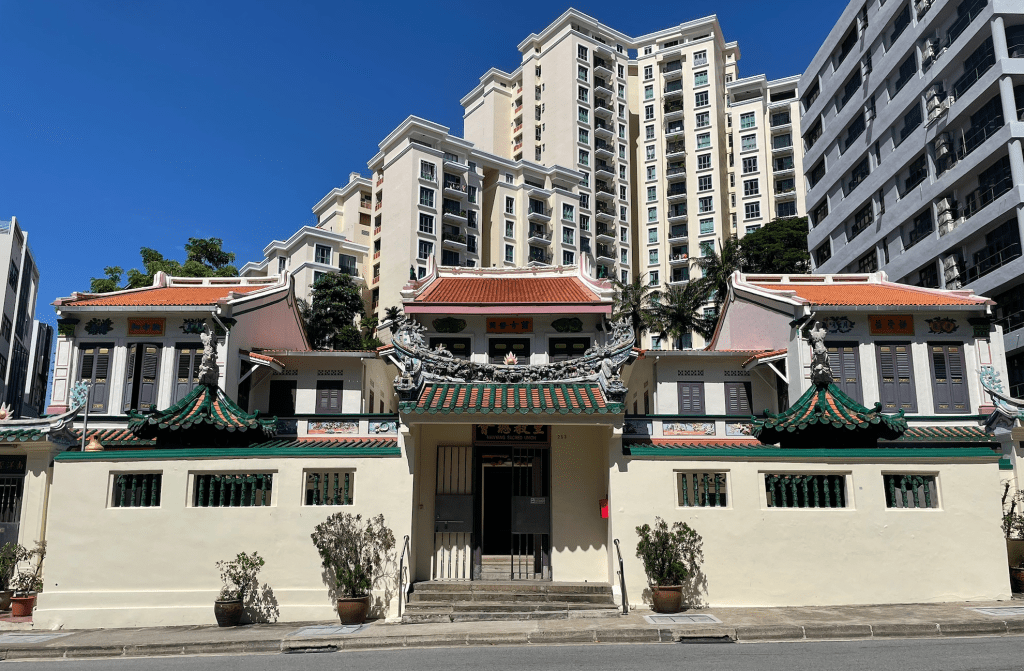

Photograph: the mysterious Nanyang Sacred Union, on Tank Road, on the far side of Fort Canning Hill from SMU, Singapore. After three years, still being surprised by the Singapore streetscape.

Leave a comment